Land touches the deepest roots of human life. It is identity, memory, inheritance, shelter, and livelihood. But across India, land is also confusion, dispute, bureaucracy, and loss. For millions, owning land should provide security. Yet in practice, it often creates stress, legal entanglement, and generational disconnect.

The Delhi government is working on a long-awaited land modernisation initiative. Every land parcel in the capital will soon receive a unique Land Aadhaar, a 14-digit identification code for deeds, rights, and records.

The aim is to reduce disputes, clarify ownership, and make the land marketplace transparent. If this system works as designed, it will become a model for other states struggling with old records and protracted litigation. The initiative is a needed step toward clarity and confidence in property transactions.

The very idea of a universal identifier for land speaks to the core problem. India’s land records have never been fully reconciled with human mobility. For decades, paper deeds, inconsistent surveys, missing maps, unclear boundaries, and overlapping claims have made land one of the most contested assets in the country.

This issue becomes more acute when we look at migration patterns. Millions of Indians born in villages have moved to cities, towns, or even abroad for education, employment, and business opportunities. These are often well-educated, skilled individuals. They have earned diplomas, degrees, and global exposure. But they also carry ancestral lands in villages that remain opaque in terms of ownership and rights.

Outdated Terminology: For the migrant, maintaining ancestral land turns into a logistical nightmare. One generation works far from the village. Another generation inherits documents that are misfiled, shared in portions, or written in outdated terminology.

The physical proximity needed to manage, survey, or regularize land never existed. Resolving disputes requires frequent travel, money, and time; commodities that migrants seldom have in abundance. Many have to rely on agents, acquaintances, or intermediaries whose motivations may not align with the family’s best interests.

Land in rural India is not just property. It is emotional capital. Scaling that emotional asset into a functional financial asset has always been difficult. Land markets, unlike digital or paper assets, are illiquid. They are slow to transact.

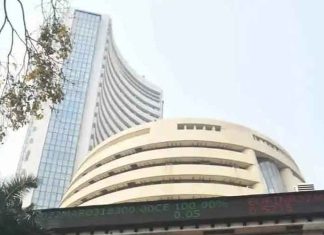

They require physical verification and countless checks. Even today, buying or selling a property often feels more complicated than trading shares or digital currencies. The friction lies not only in legal systems, but in human systems: trust, documentation, accessibility, and interpretation.

Real estate has long been marketed as one of the “solid” investments, a benchmark of stability. But when markets aren’t transparent, and records aren’t cohesive, this belief becomes questionable.

A land parcel without a clear title is not an asset, but a potential liability. The migrant who left the village to improve life for the next generation often finds that the very piece of land meant to be safety becomes a source of worry instead.

A Game Changer: The “Land Aadhaar” plan in Delhi is not a silver bullet. It does not instantly resolve fractured documentation practices across states. It does not replace the need for legal reforms or timely adjudication.

But it does signal a shift, that is, digital clarity over paper clutter, transparency over opacity, accessibility over exclusion. A unique identifier makes land records searchable, traceable, and easier to litigate or verify. This is the kind of structural change that can ease the burden on families who live far from their ancestral homes.

My upcoming book, The Fading Roots – Between Cities and Confusing Rural Lands, examines exactly this tension; the push and pull between the mobility of modern life and the fixed identity of rural land. Throughout this narrative, one thread becomes clear — rootedness without clarity becomes a burden, not a blessing.

If future generations are to live with confidence about their inherited assets, India needs a nationwide approach to land records that combines modern technology, legal harmonisation, and inclusive access.

The goal must be to let land serve its purpose — security, not stress. Land is memory. Clear records build confidence. Clarity creates choice. Modernisation of land documentation can turn confusion into possibility.